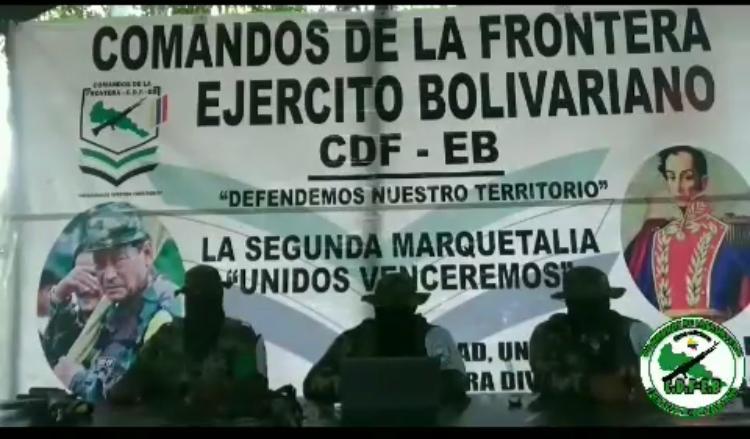

Foto: Comandos de la Frontera

Juan Pappier y Kyle Johnson

27/junio/2022

In March, 11 people died in a controversial army operation in Putumayo, southern Colombia. Human rights groups said that at least some of the dead appeared to be civilians. The army alleged the operation complied with international humanitarian law, saying that all the dead were “criminals” and that the operation had targeted an armed group known as Comandos de Frontera.

This post, which follows-up on a previous one examining the challenges in assessing Colombia’s ‘post conflict’ scenario, discusses whether there is an armed conflict between the Colombian government and the Comandos de la Frontera. It doesn’t examine whether the army operation violated international humanitarian law (IHL); rather, it analyses whether the Colombian Ministry of Defense is right to argue that IHL was applicable to the operation first place.

After presenting the “post conflict” scenario, which has been emerging since the 2017 demobilization of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas, the post characterizes Comandos de la Frontera. This analysis is critical to determine whether the operation in Putumayo complied with international law, given that IHL and international human rights law govern the use of lethal force in significantly different ways.

The relevance of this case-study goes well beyond the army operation in March or Comandos de la Frontera. It illustrates the difficulty of assessing armed groups in highly dynamic contexts, in which multiple organized armed groups operate coterminous to, and often in connection with, criminal groups. As the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has noted, the proliferation of armed groups, of varying sizes and with varying structures, capabilities, and motivations, has been a “central feature of the changing geopolitical landscape of the last decade” in conflicts around the globe.

The Current Situation in Colombia

Conflict between the government and armed groups

The ICRC and the Colombian government agree that international humanitarian law is applicable to fighting between the government and the Gaitanist Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AGC), a group that emerged from former paramilitary groups in the 2000s; and the National Liberation Army (ELN), a guerrilla group created in the 1960s.

There is less agreement on how to characterize fighting between the government and the more than 30 “FARC dissident groups,” most of which emerged after the 2017 demobilization of the FARC guerrillas. These groups often operate in the same territory FARC units controlled before the demobilization process, at times using the former units’ names. Their members mainly consist of new recruits, but also include some former FARC fighters who never demobilized and others who participated in the demobilization process but returned to arms.

The Colombian government has taken the position, since 2017, that all FARC dissident groups are parties to a conflict with government forces and subject to rules of engagement under IHL. The government treats all FARC dissident groups (which it calls “residual organized armed groups”) as a single group to which IHL is applicable—a highly questionable decision under international law.

On the other hand, the ICRC considers that only some FARC dissident groups are parties to a conflict with the government. Namely, these are what the ICRC calls “former members of FARC-EP not currently covered by the Peace Agreement.” This is a coalition led by alias “Iván Mordisco” and “Gentil Duarte,” who was recently killed in Venezuela. In our view, this coalition appears to include roughly 20 “fronts,” “mobile columns,” or units, including many that are coordinated under regional groupings they call “commands”.

Conflict among armed groups

The ICRC also considers that in three existing scenarios in Colombia fighting between armed groups amounts to an armed conflict governed under common article 3 to the Geneva Conventions. In particular:

To our knowledge, the Colombian government has not formally classified any fighting between armed groups as an armed conflict. This, however, is ultimately irrelevant since under international humanitarian law the determination of whether there is a non-international armed conflict hinges on the facts and not on any government’s classification.

Comandos de la Frontera

What we know today as Comandos de la Frontera was originally a smaller group formed in 2017 known as Los de Sinaloa and, months later, as La Mafia 48. Based on our interviews with local sources and analysis by Colombia’s Human Rights Ombudsperson’s Office, the group was formed by former fighters of the FARC’s 48th Front, as well as members of a local organized crime group known as La Constru. In late 2020, La Mafia 48 changed its name to Comandos de la Frontera. At least since 2018, Colombian authorities have publicly considered it a party to the conflict, calling it a “residual organized armed group,” seemingly due to its connection with the demobilized FARC.

Since its creation, the group has operated mainly along the border with Ecuador and has been deeply involved in drug trafficking. As one of its fighters recently told the New York Times, “This isn’t like a guerrilla that works for an idea…Everything is about the money.”

In February 2021, the Second Marquetalia and the Comandos announced in a news release that they had “held a meeting on coordination and unification of forces and political-military goals,” and that Comandos had joined the Second Marquetalia. They added that a representative of the Comandos had been included in the Second Marquetalia’s National Directorate, its highest leadership body. The announcement opens two scenarios in which the Comandos could be considered a party to an armed conflict with the government:

Option 1: Genuine links?

In our view, it is unclear whether the Comandos de la Frontera and Second Marquetalia have sufficient links to treat them as a single group under IHL.

Scholars have suggested that the relevant test to determine if such links are sufficient is whether some sort of centralized command exercises overall control over several armed groups or whether an armed group exercises such control over another armed group. At least in Tilman Rodenhauser’s interpretation, this standard does not require that the controlling group or the at least incipient centralized command be able to issue specific orders or command each military operation. But it does require all subgroups to coordinate military activities and determine the overall military objectives and the internal rules that they follow.

There appears to be little evidence of any military coordination between the Second Marquetalia and the Comandos. The only aspect that may reflect a modicum of coordination is that they rarely attack the Colombian Armed Forces or Police – a decision that “Iván Márquez” announced when he created the Second Marquetalia.

The Second Marquetalia announced in May 2021 that it had met with what it called its “southwestern units” – including the Comandos de la Frontera – to discuss the political situation in the country and reaffirm that all units present were part of the Second Marquetalia. There is evidence that this meeting did in fact take place in the Nariño state, but as far as we have been able to determine, the groups did not adopt agreements regarding coordination of military activities or their objectives and internal rules.

The clearest evidence we have been able to determine of any coordination between the Comandos and Second Marquetalia is their infrequent joint news releases (the Comandos still publish their own communiqués, without speaking for the Second Marquetalia as a whole). While these suggest that the groups might have the ability to speak with one voice, a relevant factor in the assessment, there is no clear evidence that these statements reflect a coordination of military activities on the ground as they tend to only make statements of political unity and say little about military activities.

Consistently with these findings, the ICRC treats these two groups as separate, as explained above.

Option 2

Even in the absence of sufficient links with the Second Marquetalia, Comandos de la Frontera could fulfil in and of themselves the thresholds of organization and hostilities with the government to be considered a party to such conflict.

The commandos do appear to be sufficiently well-organized. According to government estimates that we consider fairly credible, the Comandos have about 300 armed fighters, though the group claims to have many more.

The group appears to have a solid chain of command, based on their news releases and other sources. New York Times reporters who recently spent a week with the Comandos said that they:

“visited several towns under their control, watched them move weapons and buy drugs, and slept at a camp where fighters set off grenades and ran drills just yards from the Putumayo, a major river.”

Additionally, under international law, fighting between the armed group and government forces must reach a “certain level of intensity” for there to be a non-international armed conflict as IHL is not applicable to “riots, isolated and sporadic acts of violence and other acts of similar nature.” International case-law has developed a range of indicators to assess the intensity of the violence, such as the seriousness of the clashes and how spread out they are over the territory, the types of weapons used in fighting, and the number of its victims.

While the Comandos are highly armed and the Colombian government has deployed the military to the area, fighting between government forces and the armed group appears to be very rare, based on our interviews with humanitarian workers and community leaders in Putumayo. Several sources indicate that, at least prior to the controversial army operation in March, the army had not frequently attacked the Comandos. As some sources described it, they appear to be “letting them be.”

In fact, we could only identify two incidents of military attacks by the Army against the group in 2021. (A senior army officer recently told one of us that the Comandos and a FARC dissident group had engaged in fighting 27 times in the last two years, but he did not indicate how many times the government forces and the Comandos had engaged in hostilities).

This sporadic and relatively low level of violence casts serious doubt on whether fighting between Comandos and government forces can be said to amount to a non-international armed conflict. The situation, however, is dynamic and the relevant threshold could be quickly met if the army conducts more operations against the Comandos. As in other cases, the government’s classification of the fighting against the Comandos as an armed conflict could become a self-fulfilling prophecy if it leads to increased hostilities.

Some Final Conclusions

The evidence here questions the idea that the Comandos de la Frontera actually are part of the Second Marquetalia under applicable IHL. We also argue, in agreement with the ICRC, that IHL does not appear to be applicable to the fighting between the Colombian armed forces and the Comandos since it appears to fall short of the relevant threshold.

These conclusions cast doubt on the Colombian government’s argument that IHL was applicable to its controversial military operation against the group in March 2022, in which at least 11 people were killed

More broadly, our analysis speaks to the challenges of assessing armed groups in highly dynamic contexts, like the one in Colombia. The Colombian government appears to be overlooking serious legal and factual challenges that need to be taken into account to ensure that international humanitarian law is appropriately applied.

*Juan Pappier is a Senior Americas researcher at Human Rights Watch.

Comentarios: